How This Young Writer Queered Malaysia, and Possibly the World

BY LILY JAMALUDIN

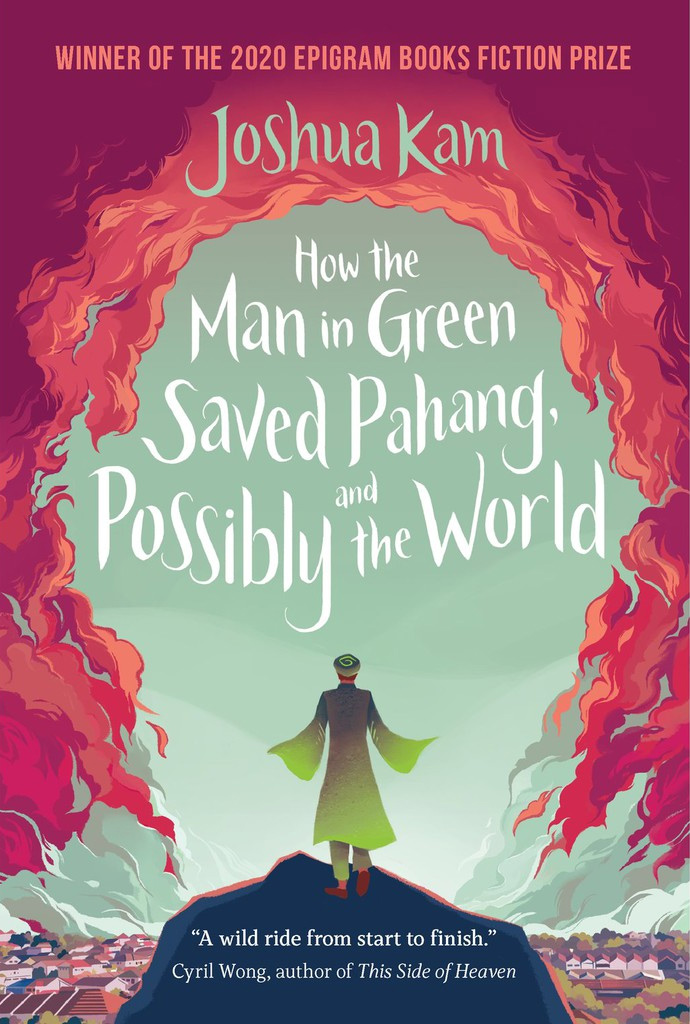

JOSHUA KAM’S DEBUT novel is an impressive feat. Wildly inventive, quirky, and philosophical, How the Man in Green Saved Pahang, and Possibly the World, tells the story of two young Malaysians who encounter history and are called to save Malaysia from a monster that threatens to swallow it completely. It’s a genre-fusing tale that integrates adventure, history, speculative fiction, magical realism, and coming-of-age themes, with queer characters that come to the forefront.

The story follows two young Malaysians, Gabe and Lydia, who are both fresh graduates of American universities and have returned back to Malaysia shortly after the GE14 elections. They carry with them the familiar baggage of young returnees: the search for identity, history, and a place in Malaysia. Gabe—overly intellectually and awkward (at times painfully so)—seems to be trying to still understand himself and find a place in a society where he feels so out of place. Meanwhile, Lydia is determined—against her father’s best wishes—to unearth the history of her beloved aunty Toh Yun, a Communist insurgent who has passed away and left behind a beautiful and daring secret.

What’s refreshing about How the Man in Green Saved Pahang, and Possibly to the World is how it is both rooted in Malaysia, but offers new imaginings of it. Joshua, who is 24 and pursuing his Master’s in South East Asian history at the University of Michigan, has situated the novel in contemporary Malaysia and given it life through layers of details of history, language, spirituality, and artistic license. It’s quite the whirlwind tour through Malaysian history. Spirits and gods become characters, architectural landmarks become sites of magic, history is given life.

“Revolutions are in the aggregate”

Joshua shows us that it is possible to imagine and re-imagine, to create and re-create the stories that were given to us, and to see ourselves reflected in the imagination of Malaysia. For this reason, Khidir’s character and sexuality will no doubt be controversial—controversy is the price paid for challenging tradition, but reviews that focus on this detail miss the forest for the trees. For me, the much greater point of Joshua’s revision of Khidir is in the act of it. It signals possibility. It is possible to create a different Malaysia—to imagine, contest, and put forth new visions of country and identity.

But what’s interesting about these reviews is that they reveal the limits of our public imagination, with readers openly exposing themselves as homophobic. This is our national and unashamed homophobia in full view—one that remains rigidly in denial of homosexuality and religion existing without conflict in the same body. Readers are saying: I tried to accept this revision, but I could not. The novel is saying: Try it. If you expand your imagination, there is so much you might be able to see.

As Joshua himself writes in the novel, “Revolutions are in the aggregate, in the many people joining up to say ‘no.’ It’s not about any one of us. And that is what we’re doing: waking the wali, rousing the sea. Growing like the roots of mushrooms in the soil.”

Lines like these—that can capture complex ideas in metaphor or near-poetry—are some of my favourite parts of the book. For example: “This was how insanity started: a willingness to concede whatever’s put before you. A complicity in the charade.” Or later in the novel, Gabe proclaims, “There are four things only in the world: beautiful truth, and beautiful lies, and ugly truth, and ugly lies.”

“I’ve kept love in my body like fire in a cannon”

Where Joshua’s writing truly shines in the novel, however, are in the letters between Toh Yun and Mo Niang. These forbidden letters, written with romance, yearning, and restraint are the most moving parts of the novel.

“Ah Girl, I’ve kept love in my body like fire in a cannon,” says Mo Niang to Lydia about her relationship to Toh Yun. “But sometimes the tip of a finger can whisper what the whole of the body wants. And it was like that—her tough, small hand snagging mine as coral snags a fishnet… Everyone pretends they invented love. It was ours a thousand years before it fell into their paws… It was always ours, even if no one knows.”

A revision of history is one thing. Two queer characters in the Communist Emergency is already a powerful statement. But to make this love irresistible, that is quite another—and I think Joshua succeeds there.

The book isn’t perfect of course. Gabe’s character, for example, left me wishing for more. Young, queer, and inexperienced, Gabe seems to be searching for the language for his body, but he never seems to find it. His newfound physical relationship with Khidir is written at times to feel like a victory, but the connection somehow feels hollow. We never get a sense that Gabe truly confronts his discomfort, or that he develops a new understanding of his body or his relationship to queerness. From Khidir, we don’t get a sense of what he sees in Gabe. It becomes easy, then, to see Khidir—older, experienced, with a noncommittal reputation—as exploitative of a young man. Gabe then becomes someone who is unable to articulate this, who perhaps mistakes a physical relationship for growth and connection—but this is unaddressed in the novel. In a community where intergenerational relationships often exist, I feel that a deeper engagement with this could have brought more to Gabe’s character in the novel.

Still, I’m excited to see what Joshua continues to write next, what themes his work will grapple with in the future. This is an impressive debut by a young and promising Malaysian writer: a novel with some truly killer lines, filled with possibility, invention, and a desire for good to triumph evil. And who doesn’t need that in these dark times?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Lily Jamaludin is a human rights campaigner and writer based in Malaysia.

“How the Green Man Saved Pahang, and Possibly the World” can be purchsed online from Litbooks or Kinokuniya.