A Divinely-Inspired Gender: The Manang Bali Shamans of Sarawak

by JOSEPH N. GOH.

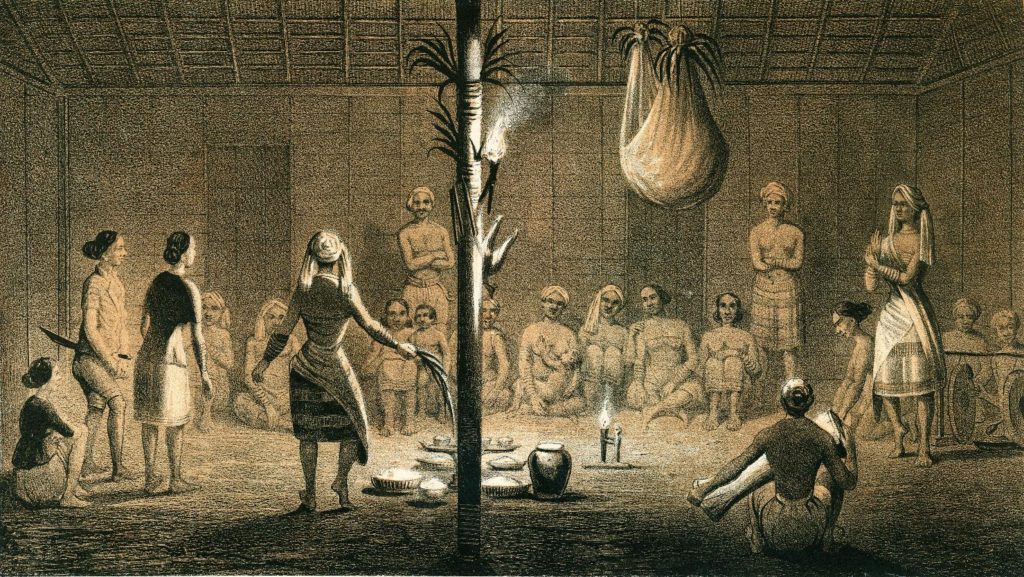

Nestled in the heart of Malaysian Borneo were the manang bali, a group of gender nonconforming shamans from the indigenous Iban tribe. They probably no longer exist due to mass conversions from animism to Christianity. Nevertheless, their historical presence holds present-day Malaysia accountable for its failure to recognise and appreciate its non-cisnormative and non-heteronormative past. The reality that the manang bali existed and were once lauded for their spiritual roles challenges and disrupts today’s state-sanctioned transphobic and homophobic rhetoric.

Spiritual intermediaries – such as shamans, mediums, witch doctors, ritualists and healers – who manifest gender non-conformity reside in many corners of Asia. These include the Ngaju Dayak basir of Indonesian Borneo, the bissu of the Indonesian Bugis people, the nat kadaw of Burma and the hijra of India.

The manang bali were one among many types of manang, albeit a minority group of shamans. They are also referred to as ‘transvestite’ or ‘transformed’ shamans, although Penelope Graham uses the latter term to denote her preference for a more open-ended approach in trying to understand these gender non-conforming individuals. This detail is important to avoid a simplistic and anachronistic interpretation of these shamans as transgender, intersex, genderqueer or cross-dressing individuals. While there were female-bodied manang bali who lived as men, the majority were biological males who lived as women.

According to existing resources, the manang bali receives directives, through dreams, from the transformed petara or deity Menjaya Manang Raja to become shamans. They must obey, or face pain of death or madness. As part of responding to their spiritual calling, male-bodied individuals adopted the mannerisms, attire and lifestyle of women, even taking on male partners as husbands. Against Valerie Mashman’s belief that the manang bali had ‘no gender and both genders at the same time’, I argue that there is every indication to show that the manang bali lived solely as women in accordance with divine imperatives. The gender and sexual transitions that occurred were integral to the initiation process of the shaman, adopting a new personal and social identity in order to serve the community. Due to these extreme requirements, the manang bali occupied the highest ranks of shamanhood.

Like other manang, the manang bali possessed a human body (tuboh). Nevertheless, as exalted beings, they were believed to have the ability to interact directly with the soul (semengat) as well as the ‘plant aspect (ayu or bunga)’ or health dimension of a person, and with spirits or ghosts (antu). Thus, they had the ability to pierce the sebayan or spirit world. The manang bali were most sought after for their healing abilities. They are said to have received this trait from their patron Menjaya Manang Raja who possessed the ‘ubat penyangga nyawa’.

Nevertheless, the manang bali did not experience unanimous acclaim despite their prowess as spiritual mediators. While they were appreciated for their services and well remunerated, they were simultaneously ‘devalued as lacking social prestige and even an object of ridicule in Iban eyes’. Iban social systems are based on strict gender binaries, and gender transitioning would not have been commonplace. Hence, the manang bali would have caused a sense of unease in the Iban communities despite their divinely-inspired gender status.

All too often, Malaysian leadership experiences a convenient amnesia about the historicity of Malaysia’s gendered and sexual diversity. Revisiting the manang bali provides an opportunity to reconnect with what Farish A. Noor refers to as ‘a deconstructive form of political history’. This form of history gives voice to a dimension of Malaysian reality that has hitherto been overlooked or suppressed, often due to – I add – narrow interpretations of religious modernity. Reconnecting with the manang bali calls to question Malaysia’s antagonistic attitudes towards citizens who either self-identify or are labelled as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, genderqueer, intersex, mak nyah, wanita keras, lelaki lembut, pengkid, cross-dresser, drag queen and queer in their myriad forms.

Gender nonconformity may not be the norm for early Iban communities. Nevertheless, they were accepting and appreciative of the Manang Bali because they realised that the transformed shamans were an integral part of their communities who had many gifts and talents to offer. What would happen, I wonder, if present-day Malaysians of all gender and sexual persuasions courageously took a leaf out of the history book of the Ibans, and learned ways of living together in mutual respect and appreciation in the midst of persistent and irreconcilable differences?

Bibliography

Barrett, Robert J. 1993. ‘Performance, Effectiveness and the Iban Manang’. In The Seen and the Unseen: Shamanism, Mediumship and Possession in Borneo, edited by Robert L. Winzeler, 235–79. Borneo Research Council Monograph Series ; v. 2. Williamsburg, VA: Borneo Research Council.

Davies, Sharyn Graham. 2010. Gender Diversity in Indonesia: Sexuality, Islam and Queer Selves. Hoboken, NJ: Routledge.

Farish A. Noor. 2002. The Other Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Silverfishbooks.

Gomes, Edwin Herbert. 2004. Seventeen Years Among the Sea Dyaks of Borneo: A Record of Intimate Association with the Natives of the Bornean Jungles. Reprint. Sabah, Malaysia: Natural History Publications (Borneo) Sdn Bhd.

Graham, Penelope. 1987. Iban Shamanism: An Analysis of the Ethnographic Literature. Occasional Paper (Australian National University Department of Anthropology). Canberra, Australia: Department of Anthropology, Australian National University.

Ho, Tamara C. 2009. ‘Transgender, Transgression, and Translation: A Cartography of “Nat Kadaws”: Notes on Gender and Sexuality within the Spirit Cult of Burma’. Discourse 31 (3): 273–317.

Howell, William, and D. J. S. Bailey. 1977. ‘Sea Dyak Witch Doctors’. In The Sea Dyaks and Other Races of Sarawak, edited by Borneo Literature Bureau, 4th ed., 159–63. Sarawak, Malaysia: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

Jay, Sain. 1989. ‘The Basir and Tukang Sangiang: Two Kinds of Shaman Among the Ngaju Dayak’. Indonesia Circle. School of Oriental & African Studies. Newsletter 17 (49): 31–44.

Mashman, Valerie. 1991. ‘Warriors and Weavers: A Study of Gender Relations among the Iban in Sarawak’. In Female and Male in Borneo: Contributions and Challenges to Gender Studies, edited by Vinson H. Sutlive, 231–70. Borneo Research Council Monograph Series; v. 1. Williamsburg, VA: Borneo Research Council.

Nanda, Serena. 1999. Neither Man nor Woman: The Hijras of India. 2nd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Sandin, Benedict. 1983. ‘Mythological Origins of Iban Shamanism’. The Sarawak Museum Journal XXXII (53): 235–50.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Joseph N. Goh is a Lecturer in Gender Studies at the School of Arts and Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia. He holds a PhD in gender, sexuality and theology, and his research interests include queer and LGBTI studies, human rights and sexual health issues, diverse theological and religious studies, and qualitative research. Goh is the author of Living Out Sexuality and Faith: Body Admissions of Malaysian Gay and Bisexual Men (Routledge, 2018), and co-editor of Queering Migrations Towards, From, and Beyond Asia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) with Hugo Córdova Quero and Michael Sepidoza Campos. His personal website is at http://josephgoh.org.