We have been brainwashed to believe this land is not queer

By VINODH PILLAI and PRITHA KHANDHAR.

Vinodh and Pritha attended the Projek Dialog event A Brief History of Malaysian Queerness last month. It featured as panelists Dorian Wilde, founder of Transmen of Malaysia, and activist Dina. The following are their reflections from the program.

‘It’s mind blowing how we have been brainwashed to believe this land is not queer’

Vinodh: I think for too long Malaysians have simply accepted the notion that LGBTIQ+ culture and ideologies are something new — a modern concoction based on “Western” theories, for example. It’s both embarrassing and hypocritical to argue that the idea of being gay in Malaysia is new, as this forum tells us, for as early as 1960, according to Dorian Wilde’s statistics, being LGBTIQ+ in our country was considered quite normal. The community, no doubt, was part of the status quo. Trans women could get legal gender change recognition by local authorities, subject to specific terms, while genderfluid courtiers and palace officials were given special privileges and statuses, and there were no special raids or segregation, as is done by officials today. One can’t help but ponder at the drastic change of events.

Pritha: Just as queer history exists in every nook and corner of the world, Malaysia was no exception. However, I simply had not realised how prominently the queer community featured in Malaysian history as compared to present-day Malaysia. I had always thought the current marginalisation of the LGBT community was the result of a change in political opinions that permeated into our culture. If my lack of knowledge is the same as that of my peers, then we are truly ignorant of our queer history and how it intertwined with contemporary politics. Coming out of this forum, I found that the pace as to which this shift took place extraordinary. But equally extraordinary was how queer people found their place in Malaysia.

‘Who said LGBT Malaysians don’t know politics? We’ve got a voice, and it’s loud’

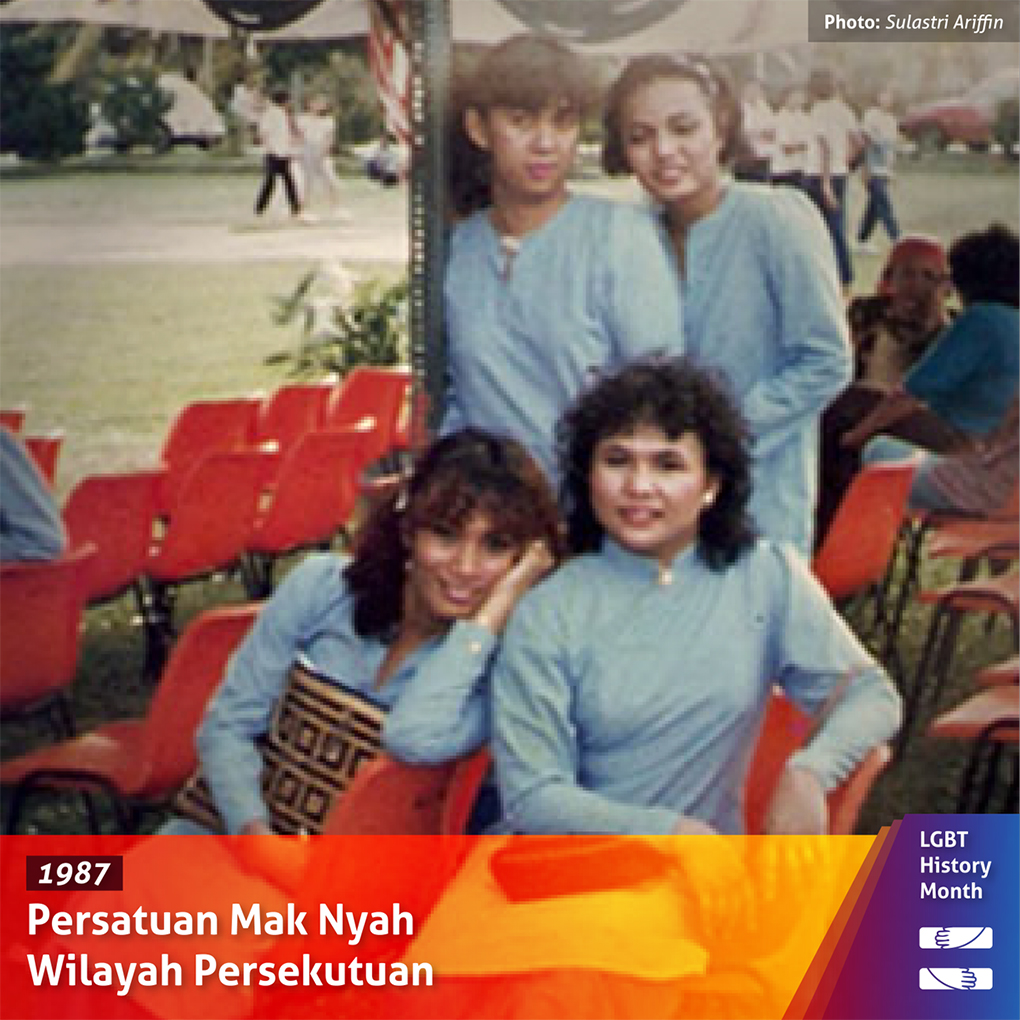

Vinodh: I was honestly very surprised by the level of maturity of those in the room. You don’t often see this kind of unity and level of discussion with LGBTIQ+ people. At the forum, for example, one of the questions asked was whether it would be worthwhile today to reclaim the statuses held by LGBTIQ+ Malaysians of the 80s. This garnered unfavourable responses from the audience of mostly trans individuals. When told about the Persatuan Mak Nyah Persekutuan, a federal organisation under the BN government that took care of transgender people, not many seemed keen at the idea of its revival. One found the idea of a “party” of sorts just for LGBTIQ+ people discriminatory, while another conceded that even with special privileges and rights for LGBTIQ+ people, without recognition of human rights, it was a big no-no. One individual quipped that it didn’t seem relevant to have a party to learn sewing or patchwork – which is what the party did for trans people then. It’s a clear sign that LGBTIQ+ Malaysians are politically aware, and deserve as much attention and recognition as their heterosexual counterparts.

Pritha: To be honest, once the discussion took a political turn, I was as equally captivated as I was lost; captivated because the discussion was so incredibly lively, but lost, as I was rather unfamiliar with the political workings of our country. Yet, the sole reason that discussion remains inspiring is that all the voices spoke out in unity. While opinions within a community may differ, there was unity in the sense that there was respect for one other, and there was consensus that they deserved the same rights as cisgender and heterosexual people. I was very impressed.

‘Visibility and dialogue is all good, but what about when anti-LGBT groups do the same thing?’

Vinodh: Historically, it’s clear that Malaysia should be fine with LGBTIQ+ people. Hence, it is sad that we are drifting away from this ideal that was considered the norm just thirty to forty years ago. But is dialogue necessarily the best means of broaching the subject today? Look at all the talks and “anti-LGBT” forums that local universities and NGOs constantly hold to set the record “straight” about being gay – according to them. Think of the news reports and articles as well that get churned from these events – they don’t do much to defend or portray the LGBTIQ+ community in good light, and yet the collective goal is to turn the taboo topic into a talking point. Don’t get me wrong; I don’t think we should stop having talks and open forums. I’m just wary about how we can help the other side sort things out – if we don’t dialogue with each other. How do we justify that speaking out constantly on the matter will eventually do good for all?

Pritha: This existence of this event itself proves that, yes, there is dialogue, and judging by the audience (like me!), it does extend to those outside the LGBTIQ+ community. And it goes beyond raising awareness about the existence of the queer community. It is also about listening to them as they communicate their struggles and tell their stories. However I do feel that this rising voice exists in only small pockets within our society. These small, but fierce voices do not mean that the tide is a losing battle, but I don’t believe that the LGBTIQ+ community on its own is able to deter the current narrative being presented through mainstream media – not that I’m placing blame solely on LGBTIQ+ activists and the community as a whole. The only way perhaps to change the content of our mainstream media is to enlighten the minds of those producing and distributing the content.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Vinodh, 21, is a writer for Queer Lapis, and an aspiring journalist. Pritha, 20, is a gender studies major from Monash University.

This event took place at Projek Dialog’s office in Petaling Jaya on Wednesday 21 February.