A Reformist’s Prayer: May a Rough Ramadhan Turn into a Redeeming Raya For All

By SURI KEMPE

AS A CHILD, I went to a religious school next to the village mosque. During Ramadhan, students would be pulled in to help as cows were slaughtered. I have a distinct memory of cleaning cows’ stomachs, running my hands over the white, rubbery, bumpy texture. Little-Me was grossed out. But I would remember that the bubur lambuk daging we made from it was for anyone who came to the mosque: all were welcome, no questions asked. The neediest, in particular, would be taken care of.

I felt a little bit better about cleaning this weird animal part knowing that the many people who sat around the mosque’s compound—often migrants who had ended up on our shores, some of whom were women holding children in their laps—would go through at least the next couple of days not having to worry about food.

As I grew older, though, this idea of Ramadhan as a time for Muslims to be in the service of those in need has become tainted. As I became more engaged with what was going on around me (yes, I grew up and became an activist), Ramadhan slowly began to change. It became a time when people became overzealous in their religiosity and cruel in their actions.

Who is a good Muslim?

Each year, anyone who doesn’t fit into this pre-determined, narrow idea of who is a good Muslim becomes a target. In 2013, a Muslim woman who ran a dog rescue centre and had posted an Eid greeting with her dogs was harassed. Several years ago, an iftar event organised for LGBT Muslims promoting inclusion was met with derision while the organisers received death threats. There always seems to be one reason or another for Muslims’ fragile toxic religiosity to rear its ugly head.

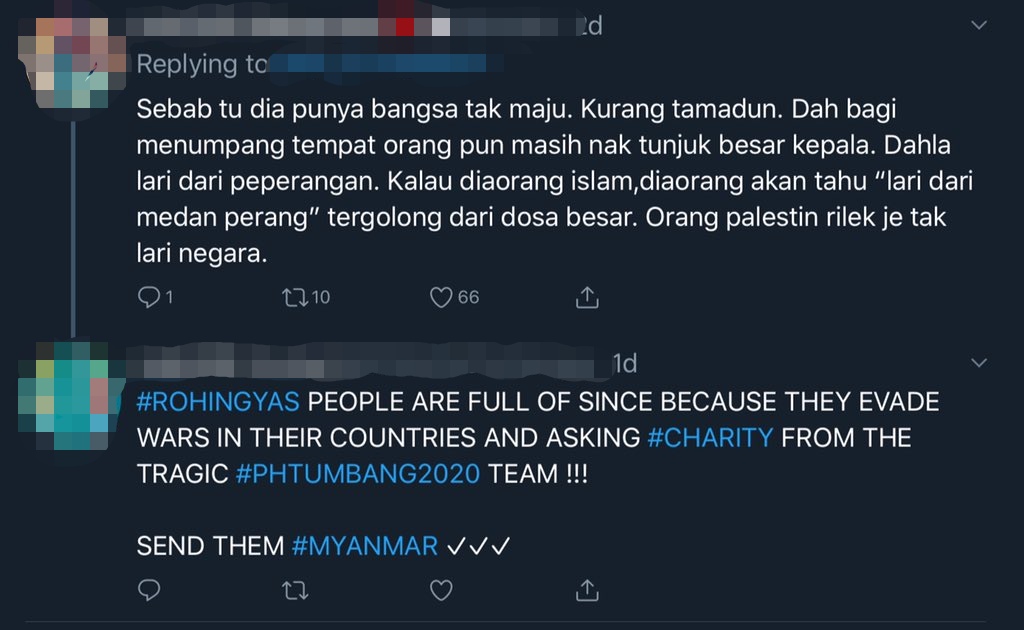

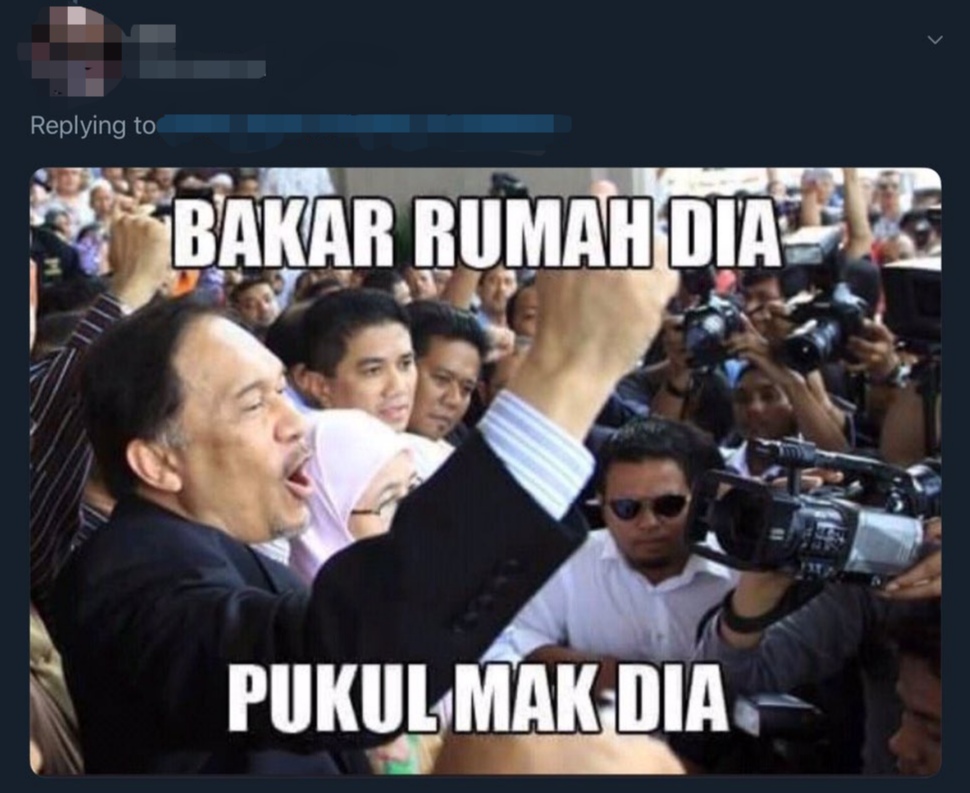

This year, migrants, including women and children, seemed to be the flavour of the month. All migrants, particularly refugees and the Muslim Rohingyas, quickly became the target of xenophobic and violent comments on social media and even online petitions calling for them to be deported, many made by Malay-Muslims in this country. The authorities have also conveniently used the pandemic as an excuse to raid, arrest and detain migrants, including young children, as a means to “contain the spread of the virus.”

On the flipside, there were many Muslims and good people who coordinated food, shelter, and healthcare for migrants and refugees, who stood up against the mistreatment of migrants, and who organised and took part in the #MigranJugaManusia online protest. But it’s difficult to pretend that these wonderful efforts weren’t met with more backlash, hate speech and threats.

The spirit of justice

Because Ramadhan is supposed to be a time to do good, the xenophobia, racism and bigotry expressed by Muslims become even more stark. I often find myself asking: how Muslims who behave like this don’t see the utter hypocrisy of it? Do they fast, perform prayers five times a day, read the Qur’an a little, and then in between sneak off to the cyberworld to spit venom at anybody who isn’t like them? Dah habis sesi membenci? Ok, jom buka puasa.

I will confess that more often than not I struggle to see the spirit of justice in Islam when the behaviour of my fellow Muslims reflects such ugliness. It’s worse when they actually bandy about religion to justify their bigotry and cruelty. In attempts to contain my disillusionment, common sense tells me to separate the behaviour of Muslims from the religion itself. Confirm diorang je yang tak senonoh ni; bukan salah agama. But there are only so many times you can say that without feeling like an apologist. I needed something more.

Being born Muslim, we inherit our faith, which perhaps makes us somewhat complacent when it comes to examining ourselves and how we embody our faith. Being a feminist, queer woman, and a mother, however, has forced me to interrogate my own faith, because faith, as it turns out, is dynamic, and constantly shifting. It needs to be balanced between what I see in the world outside and what I feel inside. My relationship with God, like any other relationship, needs to be nurtured to grow.

Quest for reconciliation

This quest for reconciliation has led both inward in search of myself and outward in search of knowledge. It has helped me find a path of understanding Islam through an ethically oriented reading of the Qur’an, one that aims to deconstruct and challenge the patriarchal assumptions that hold sway over mainstream interpretations.

I know with certainty that God did not say, accept only those like you, or be kind only to those like you. The Qur’an states that we are all created equal—from the same essence, the same soul (nafs wahîda). But humankind was also gifted with diversity, and They created us in all our diverse glory, so that we might learn from one another (I use the pronoun ‘They’ to refer to God intentionally, because in the Qur’an God refers to Himself/ Herself/ Themselves using various pronouns, so don’t trip):

Surah Al-Hujurat, verse 13 in the Qur’an reads, “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another” (49:13).

The reform trajectory

A friend recently wrote that “in these difficult times, it’s important to remind ourselves of the Qur’an’s reform trajectory, which focuses on those who are oppressed. We are constantly reminded of our blind spots, عَبَسَ وَتَوَلَّىٰ* you frowned and turned away* (81:1), and reassured that God is listening to us, that God is with the rebelling voices of the oppressed, قَدْ سَمِعَ اللَّهُ قَوْلَ الَّتِي تُجَادِلُكَ * “God has indeed heard the utterance of she who argues with you …” (58:1)”

I am reminded that the core of the Qur’anic message is to stand for justice, to seek beauty and to do good. My relationship with God is tied to manifesting these values in my communities, and I am humbled to be able to do this through my activism.

We are living in a unique moment in history. All across the world, the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the inequalities among us, and it has shown how the most vulnerable among us—refugees, migrants, LGBT people, the poor—are impacted more severely. They have the least access to resources, and no adequate protections under the law. Some even lack the support of their families.

While the holy month of Ramadhan may have come to an end, the call for compassion does not end here. This is an opportunity for us to collectively reflect on how we can correct the injustices we have inflicted upon one another, to reach out to those with whom we share this space and build community with them. Perhaps the compassion we must learn can only come from the lessons that the outcasts and the oppressed can teach us.

Selamat Hari Raya, and Maaf Zahir Batin, everyone.

—

Suri Kempe is a Muslim feminist working with Musawah and is one of the founders of Queer Lapis. She wants to add something quirky to this bio but she can’t do quirky on purpose; she’s quirky by accident.

We Understand the Pain: LGBTQ Malaysians Speak Up for Migrants & Refugees

On this May Day, I think about the barbed wires that coil around us all